Art Directions: A Constellation of Moving Images

Thirty years ago, IFFR took a leap by introducing a programme defined not by format, but by curiosity. With the launch of Exploding Cinema in 1996, the festival posed a question that continues to resonate today: what can cinema be when it moves beyond the limits of the film theatre?

Emerging at a moment when digital technologies were entering cultural life with both optimism and disruption, the programme became a testing ground for works that moved between film, visual art, sound, performance and new media. Over the decades, this exploratory impulse evolved through Cinema without Walls and Frameworks, forming the foundation of what is now Art Directions. Not as a departure from cinema, but as a space where cinema is continually examined, expanded and reimagined.

Art Directions 2026 builds on this lineage while firmly grounding it in the present. Rather than looking back nostalgically at earlier moments of experimentation, the programme treats history as a living resource, activated in response to contemporary urgencies. This year, cinema within Art Directions functions as a multidimensional instrument: a means of transformation, research and connection that unfolds across installations, immersive media, sound//vision works and live performances. These formats do not exist in isolation, but form a constellation of filmic practices that reflect how storytelling is shifting today.

Across this constellation, film operates in multiple ways rather than pursuing a single agenda. Some works focus on bodily and emotional experience, allowing release to occur without narration. Others return to memory, working with personal and historical material that continues to shape the present. Elsewhere, film becomes a means to visualise inner worlds or acts as a call to awareness, confronting viewers with political, social and ecological realities that demand attention. What connects these approaches is not a shared theme, but a commitment to cinema as an active process of inquiry.

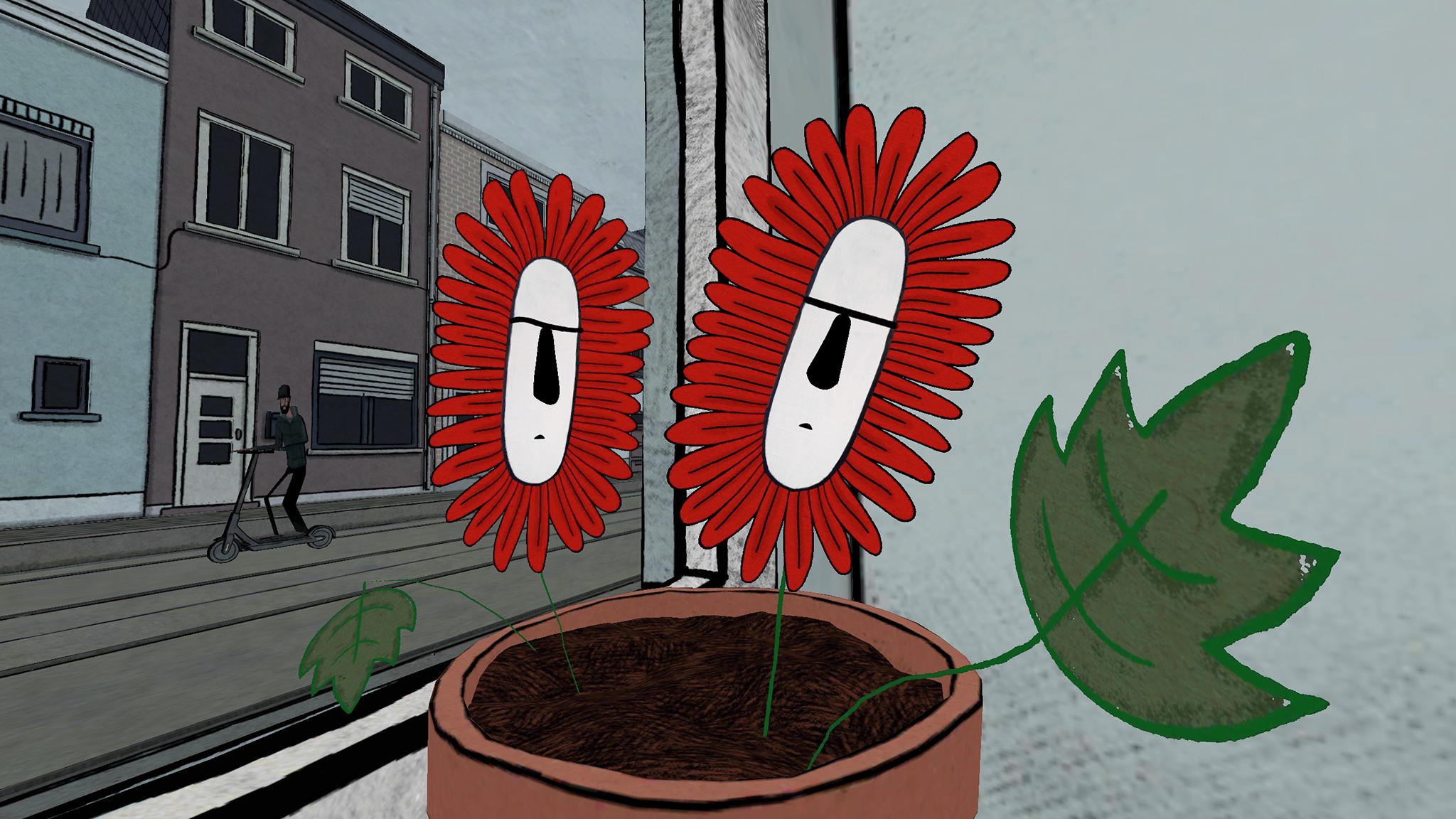

Several works approach memory and storytelling through shifts in perspective, asking what happens when cinema no longer centres the human gaze. In If You See a Cat, the story unfolds entirely from the viewpoint of a cat, as a way of approaching experiences that resist direct representation. The animal perspective becomes a lens through which loss, mental illness and forced institutionalisation are observed obliquely, with intimacy and care. The Great Escape offers a similarly displacing perspective, inviting audiences to experience space through the eyes of an escaping houseplant. In both works, immersion is used to gently unsettle perception, expanding cinema’s capacity for empathy by reconfiguring how and from where a story is seen.

Elsewhere in the constellation, artists engage with archives as living material rather than static records. Tosca Schift reinterprets a colonial journey from 1958 through a family archive stored in biscuit tins in It’s Too Cold for the Spirits to Live Here. In the installation Café Kuba: Who Dared to Awaken the Dead Memory, David Shongo presents Kinshasa as a city where unresolved histories continue to echo through public space, even as new forms of resistance and creativity emerge. Seen together, these works treat memory as something continually rewritten through images, objects and voices.

At the same time, several artists explore the machine as a creative partner rather than a dystopian threat. In Alterity, presented as both a performance and an installation in Brutus, Jacco Gardner enters into a dialogue with his Macintosh ensemble through the rare software Trip a Tron, developed by early game pioneer Jeff Minter, treating the computer as an unpredictable collaborator. The Great Orator, an immersive work by Daniel Ernst, creates a shared consciousness in which an AI-generated narrative shifts in real time through interaction with the visitor. Nan Wang combines 16mm footage with AI processes in Echoes Between Seeing #3 to produce landscapes that hover between documentation and hallucination, questioning where authorship and agency reside.

The ecological crisis and the condition of the anthropocene form another urgent thread. In Krakatoa Carlos Casas reflects on contemporary climate anxiety through the historical eruption of the volcano in 1883, presenting the work as film, installation and live performance, where sound becomes a physical force felt in the body. In The World Came Flooding In, climate collapse appears not as spectacle, but as lived aftermath. This immersive project reconstructs domestic spaces, showing us how flooding reshapes memory, space and identity, revealing extreme weather as a recurring condition rather than an exception. In Hydrotopia, ecological transformation is rendered materially tangible through the slow dissolution of a frozen body, foregrounding impermanence and non-being. Together, these works approach environmental crisis through force, residue and alteration, shifting attention from catastrophe itself to what it leaves behind.

Throughout the programme, film increasingly adheres to the body. Cinzia Nistico presses human skin and hair directly into the film emulsion of DISINCARNATE, asking whether a trace can become a form of life. Jana Stallein makes structural violence palpable in VR docufiction After the Game by allowing visitors to explore abandoned belongings of refugees trying to cross the Bosnia-EU border. Cycle uses embodied experience within a virtual environment to evoke the cyclical nature of existence, shifting perception from observation to sensation.

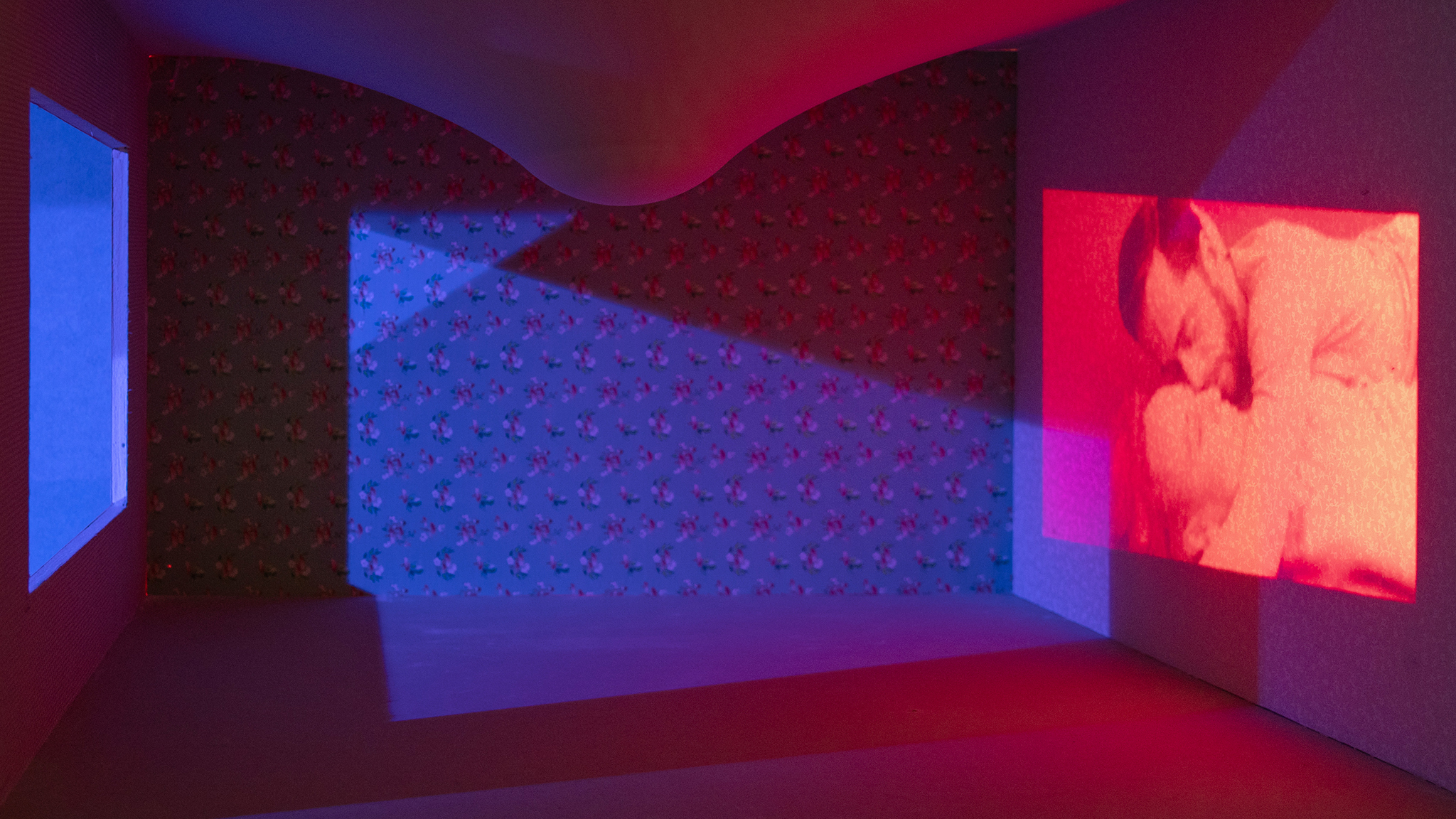

Cinema also repeatedly breaks out of its architectural confines. In 3 Scenes from a Marriage, an installation by artist duo Leopold Emmen (Nanouk Leopold and Daan Emmen), furniture and walls are transformed into thresholds within a non-linear cinematic space, making time and intimacy physically navigable. In Preludio by Silvia Gatti, space itself becomes an interior landscape, where sculptural elements, sound and image dissolve narrative into sensation, allowing memory and emotion to surface beyond language. This outward movement continues beyond Katoenhuis, this year again serving as the central hub for most installations and all immersive projects, as several works deliberately embed themselves within the city itself, activating public and institutional spaces as cinematic instruments.

With Raftsmen and Canoeists, cinema enters the everyday rhythms of Rotterdam Central Station via the Kijkmodule presented in collaboration with Museum Boijmans van Beuningen. Situated in a space defined by transit and temporality, the work interrupts habitual movement with a moment of attention. Film here is neither destination nor spectacle, but an encounter that emerges in passing, collapsing the distance between cinematic time and lived time. At Plein in Fenix, the new art museum of migration, My Sweet Elora inhabits a public square shaped by layered histories of departure, return and displacement. Its intimate use of personal archives resonates with a site where private stories and collective trajectories come together. Homecoming, presented at the Nieuwe Instituut, situates its inquiry into technology, ecology and estrangement within an architectural context devoted to design and the future, sharpening cinema’s role as critical reflection rather than illustration.

Immersive media in all shapes and forms plays a central role within this expanded field at IFFR. Virtual reality, immersive installations, interactive environments and generative systems introduce narrative possibilities that are as significant as any earlier cinematic format. 2026 marks the launch of Lightroom, IFFR’s new industry platform for immersive storytelling. Lightroom brings together XR, VR and interactive projects previously presented across CineMart and Darkroom into one unified space, hosted at Katoenhuis and developed in close dialogue with the Art Directions programme. IFFR positions itself as a place where these emerging languages are not only presented, but critically examined and shaped, including through this year’s Reality Check: Lightroom symposium. As with Exploding Cinema three decades ago, artists and audiences alike find themselves navigating unfamiliar terrain, where the grammar of the medium is still being written.

Art Directions today is therefore an essential breathing space within the festival. A place where cinema can pause, stretch and test its limits, without the pressure of immediate resolution. Like a constellation, it offers no single route, but invites audiences to trace their own connections between works, spaces and ideas, and to not only watch, but to inhabit, to listen and to reflect. Thirty years after the first explosion, the core impulse remains unchanged: to stay open to what cinema can become, precisely at the moment it leaves its familiar frame behind.

– by Eva Langerak

A list with articles

-

IFFR closes its 55th edition celebrating an uptick in new, younger audiences and industry attendees

Published on:-

News

-

Press release

-

-

Shahrbanoo Sadat’s No Good Men opens Berlinale 2026 among strong HBF and CineMart lineup

Published on:-

CineMart

-

Hubert Bals Fund

-

IFFR Pro

-

-