Tetsuya Maruyama: Expansion/Contraction

With Focus: Tetsuya Maruyama, IFFR 2026 spotlights the work of the Rio de Janeiro-based Japanese multidisciplinary artist. IFFR programmer Cristina Kolozsváry-Kiss takes an in-depth look at Maruyama’s background and approach to cinema.

Tetsuya Maruyama’s (Yokohama, 1983) work is an endlessly blurred line between practices, aesthetics, cultures and spaces. Uniformly across all of his works is an ambition to do the absolute most with the absolute least; an art and filmmaking ethos that is nimble, resourceful, practical and clever. This extreme economy of means makes his work difficult to describe, as the meagreness of the materials do not render the spectacle of the event; because what also binds his work together is an emphasis on space and time that requires presence in a singular moment. Even works of written text or found sound mixtapes are meant to be experienced collectively, and often Maruyama’s goal is to expand a cinematic moment while collapsing the cinema space.

This expansion and contraction often takes rather quotidian starting points, but before I explain what I mean and how he does it I should interject with a bit of biographical information. Maruyama is a Japanese artist who comes to us by way of Rio de Janeiro where he lives with his family, so quotidian for him would seem quite exotic and fabulous to your average mid-winter cinema-goer in Rotterdam. Do keep that in mind when palm trees and beach scenes flicker by on celluloid, as in Maruyama’s palm tree-punctuated pinhole experiment, Q&A, and in Gira 2 which features two super 8 cameras attached to the pedals of his bike as he cycles along the coast. For him these are regular places and commutes, no different from my regular bike ride to Centraal Station in Amsterdam, though with noticeably more people wearing remarkably less clothing.

It’s also worth noting that Maruyama has a background in architecture, having studied it at the University of Buffalo before working as an architect in Portugal, Japan, Haiti and Brazil. That influence is clearly seen in works such as Corredor, a single take of a hallway exploring that often neglected but functionally essential space within buildings. It’s also noticeable in his performance One more performance that unfolds a space, where Maruyama investigates the cinema space without the presence of the projected image. A distillation of space is combined with the analysis of time in his film Shashin no Ma, 間 (MA) being a concept in Japanese aesthetics that translates as space, pause or interval but is difficult to convey accurately in English. The film (like the concept) explores the idea of emptiness as both a spatial concept but also a temporal and visual one.

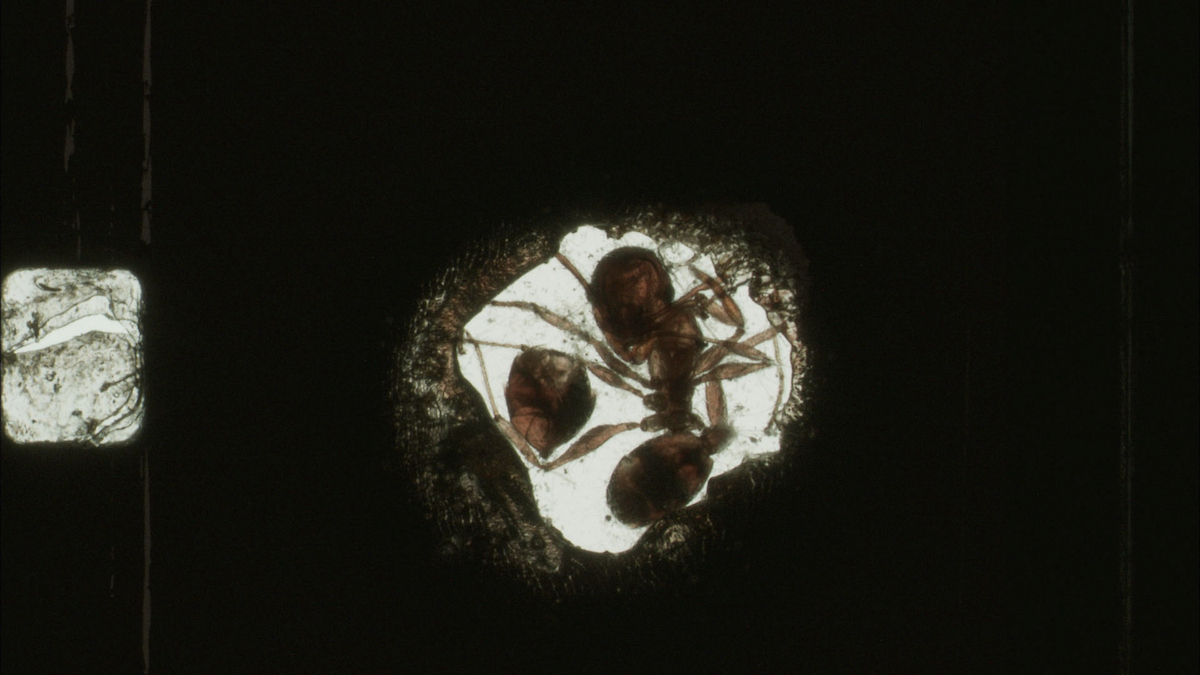

This reductionist approach to cinema goes beyond time and space and extends into the actual production of his films. There are, of course, financial limitations and obstacles to accessing materials and equipment in the Global South that necessitate a leaner, thriftier approach to moving image-making. But Maruyama sees this as an opportunity, exploiting such limitations to creative ends. Aside from working often with super 8 (the small gauge is apparently quite popular among contemporary Brazilian filmmakers for reasons already mentioned), he’s also known for his cameraless works such as ANTFILM which places the corpse of an ant in a burned-out hole in a single frame out of every 24; or L.O.V.E.S.O.N.G, which appropriates a found super 8 cartridge that once contained footage of a Jewish wedding now bleached beyond recognition.

In his larger gauge (16mm) expanded cinema piece, Untitled (three moons), Maruyama uses the light passing through spheres on black leader to reveal the inconsistencies of the projector apparatus. Even more spartan is his performance Situation-Cinema, in which he invites the audience, via prompts, to create cinema so expanded it leaves behind the viewing experience altogether, answering the question “What is film?” with things as banal as a lamp post. With Third Mountain Maruyama uses found 35mm slides from the archives of a mining company as part of an ongoing investigation into the aesthetics and impact of mining sites. This investigation also includes the expanded cinema performance Pedra e Montanha which takes place in our Art Directions sound//vision programme, incorporating these 35mm slides into a multi-projector performance with live sonic accompaniment by Robert Kroos.

All of the works mentioned above take a very roundabout and creative route to the filmmaking process, from found materials to cameraless works. In his contemporary structuralist explorations of single-channel celluloid and expanded cinema Maruyama is always, in fact, reducing films to their most elemental components, challenging the very notions of spectacle and spectatorship long taken for granted. At the same time, he’s deconstructing cinema into bits and pieces, fragments of the whole to be investigated individually before being reassembled. Here we return to the idea of the quotidian, which reflects not only the materials he uses and the spaces he captures but also the way in which he invites us to explore cinematic spaces and the ‘cinematic’ in spaces we inhabit every day, mostly unaware. Fitting then that Maruyama would point me to a quote from Anthony McCall made in reference to McCall’s seminal 1975 film-less film Long Film for Ambient Light: “It’s as though filmmaking had led you out of film”.

Aside from filmmaking, Maruyama also works as a curator, most notably programming tours of contemporary Brazilian filmmakers that have played across the United States, Latin America and Japan. He is an ardent advocate for the importance of shared screening spaces and experiences, which is why his work would be difficult to see or know about if he himself didn’t happen to come to your city or town with a bundle of reels under his arm. It’s for this reason that we are delighted to have him here for two screening programmes and a performance that could only exist once in each space, changing each time with each different screening room, be it black box or white cube, and changing with each constellation of audience members sharing these moments of suspended time.

– by Cristina Kolozsváry-Kiss

A list with articles

-

IFFR closes its 55th edition celebrating an uptick in new, younger audiences and industry attendees

Published on:-

News

-

Press release

-

-

Shahrbanoo Sadat’s No Good Men opens Berlinale 2026 among strong HBF and CineMart lineup

Published on:-

CineMart

-

Hubert Bals Fund

-

IFFR Pro

-

-