Reflections on Colonial Pasts and Possible Futures

The IFFR 2026 Focus programme on Collectif Faire-Part celebrates the work of the ensemble of Belgian and Congolese artists. IFFR programmers Lyse Nsengiyumva and Koen de Rooij take an in-depth look at their work and practice.

Collectif Faire-Part’s core members Paul Shemisi, Anne Reijniers, Rob Jacobs and Nizar Saleh came together some 10 years ago with the shared desire to tell stories about Kinshasa – a city filled with history, struggle, art and endless narrative potential – and to explore the complex relationship between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Belgium. The question arose: which stories to tell, and how to tell them?

Their 2019 work Faire-part, being their longest film to date at nearly 60 minutes and sharing its title with the collective’s name, can be considered a centrepiece in their practice and is crucial for discussing and understanding their body of work. One part of the film, which consists of the portrayal of a variety of political street performances throughout the city, manages to capture the atmosphere in Kinshasa’s streets. Ranging from the performative washing of flags of countries that played their part in colonial history, to the construction of the Congolese map from old, discarded mobile phone cases, we observe a variety of artists shifting between the 30 June celebration (Independence Day in the DRC) and their struggle with what colonialism has left behind in this city – a struggle that is far from finished. On the other side of the camera, we witness the interaction, discussions and reflections among the collective’s members. While they discuss how to make the film, what stories they want to tell, and how they want to position and present themselves, we come to understand quickly that making films about Kinshasa is not easy, for both practical and ideological reasons.

It is in these discussions between the members that we find an entry point into one of the central elements of Collectif Faire-Part’s practice. Faire-part, it turns out, is a meta-film because it has to be. It cannot be anything else. To make a film about Kinshasa as a collective is to discuss what it means to make a film about a colonial past, about its continuing influence in the present, about how to approach and tell these stories and what it means for two European filmmakers and two African filmmakers to collaborate in this way, born continents apart but tied by history. By inviting us to reflect on this collaborative process with them and, perhaps even more essential, by showing us they also do not have all the answers to the questions they pose, that they are figuring out how to navigate this complex reality as well, they create a space for us to be in dialogue, with them, with ourselves, and with others. This dialogue, and the space the collective creates for it, forms the core of much of their work.

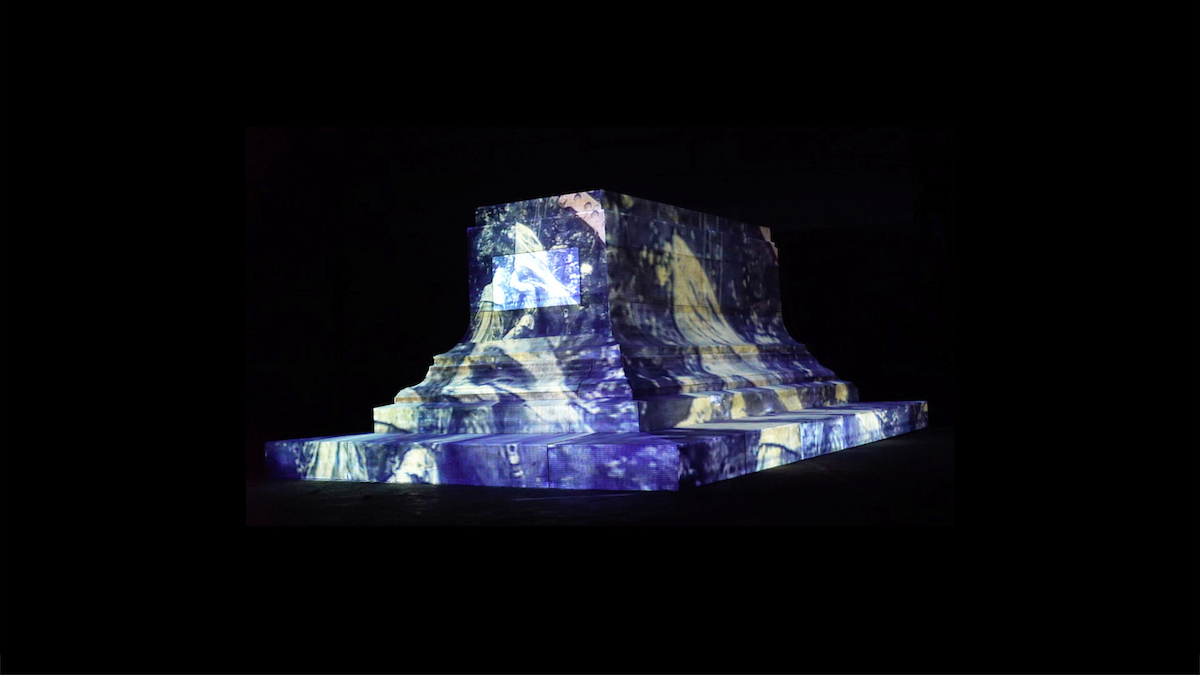

Whereas their early works mainly revolved around public spaces in Kinshasa, the collective’s more recent work increasingly sees them expanding their focus outside of the DRC. Speech for a Melting Statue (2023), a film inspired by the protests that happened in June 2020 in Brussels against police brutality and institutional racism, emerges from the feeling that the statue of Leopold II could have been taken down by demonstrators at some point. The film is propelled by a speech by poet Marie Paule Mugeni, which she’s already prepared for the day when the statue of Leopold II is actually removed – just in case. As we hear her talk, we see archival footage of colonial statues arriving at a museum in Kinshasa, confronting us with the fact that this change has already happened elsewhere, and making us wonder how easy it would be to accomplish it here as well, if only Europe could free itself of its colonial mindset. Recalling a remark Nizar Saleh makes towards the end of Faire-part – “We talk about the past, the present, but we have forgotten about the future… “– we realise that speculating about a different future becomes essential for capturing the present and dissecting the past.

The collective’s work becomes increasingly personal in two other films included in the retrospective, since the core of both L’escale (2022) and their newest film What We Said to Brussels Airlines (2026) consists almost entirely of discussions between the collective’s members that reflect on their own experiences. In What We Said to Brussels Airlines, the members consider a proposal they received from Brussels Airlines to screen their film(s) on the in-flight entertainment system. The first half of the film consists of the collective’s members weighing up the pros and cons of screening their work on board and questioning the social role and moral responsibilities of a large company such as Brussels Airlines.

The visual language used in the first half of What We Said to Brussels Airlines is very similar to that used a few years earlier in L’escale, and their response to the airline cannot be seen separately from the experiences related three years previously. L’escale, a film that consists in its entirety of footage shot through an airplane window, narrates what happened to Nizar Saleh and Paul Shemisi at Luanda airport during a layover on the way to Europe. As we watch the endless stream of clouds and skies that accompanies their testimony, we are confronted with the fact that the freedom to move around – which many of us take for granted – is still only available to a limited segment of this planet’s population. L’escale tells of a nightmare that could happen to the same band members we follow in Kingongolo Kiniata (2024) every time they travel to Europe to perform. These films contribute to a larger debate on the struggles and complexities faced by artists in obtaining visas.

This back and forth between more direct, personal and emotional reflections and wider power dynamics creates a tension that is present in all of their works. As these images and stories connect to each other throughout the collective’s work, they remind us how colonial mentalities continue to shape the world and formulate the rules by which its people and institutions are bound. If Kinshasa is a “theatre without end”, as one of the street performers in Faire-part remarks, so is Antwerp, so is Brussels, Belgium and the rest of Europe, all in their own but related ways. Drifting between reality and fiction, between the colonial past and its traces in a still foggy future, between unclear rules, uncertain political situations and vague official statements, the collective’s films seem to remind us that what will happen next is not just up to large institutions or the people in power, it is up to us as well.

– by Koen de Rooij & Lyse Nsengiyumva