Cinema Regained: All the Pasts Possible

Each year, the Cinema Regained programme spotlights restored classics, documentaries on film culture and explorations of cinema’s heritage. IFFR programmer Olaf Möller guides us through this year’s selections.

“To history has been assigned the office of judging the past, of instructing the present for the benefit of future ages. To such high offices this work does not aspire: it wants only to show what actually happened.” These are probably the most famous lines found in Geschichten der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1514 (1885) by Leopold von Ranke, one of the founding fathers of modern history. It is still not completely clear what he meant by “actually happened”: whether this goes beyond sticking to sources, and in what way? One even has to ask: which sources – what does one deem relevant enough to consult?

Cinema Regained is driven by an interest in works and tendencies less widely discussed, sources rarely consulted – sometimes because the films are deemed not artistic enough by the high arbiters of yore, at other times because they come from cultures too long marginalised and/or exoticised. Joseph Cates’ Who Killed Teddy Bear? (1965), for example, might be a prime piece of US exploitation cinema, but very self-consciously so. Cates shot scenes for his deeply disturbing stalker noir with a sharp giallo undertow at some of the spaces the film was destined for – the cinemas at Times Square and 42nd Street where the more daring works of European film art shared screens with homegrown gutter genius whose sole intention was to turn a buck. Who Killed Teddy Bear? is a fusion of both, a 94-minute digest of cinema at that moment in history – its extremes forced into a single shape.

A whole city’s dream life is on display in Romano Scandariato’s L’ammiratrice (1983), featuring one of the biggest stars of Naples popular culture, singer-actor Nino D’Angelo, whom IFFR audiences can get to know thanks to Nino. 18 giorni (2025) by his son, Toni D’Angelo. L’ammiratrice is a sceneggiata, a musical melodrama (usually) in Neapolitan dialect, which is a crystallisation of the way the city loves to see itself – a documentary, of sorts, of a collective self-image. What makes L’ammiratrice particular in this context is Nino D’Angelo’s role as a singer called Nino D’Angelo – a genre re-imagination of himself that feels as real and of documentary value as the newsreel and home movie images woven together from decades on stage and screen by his son.

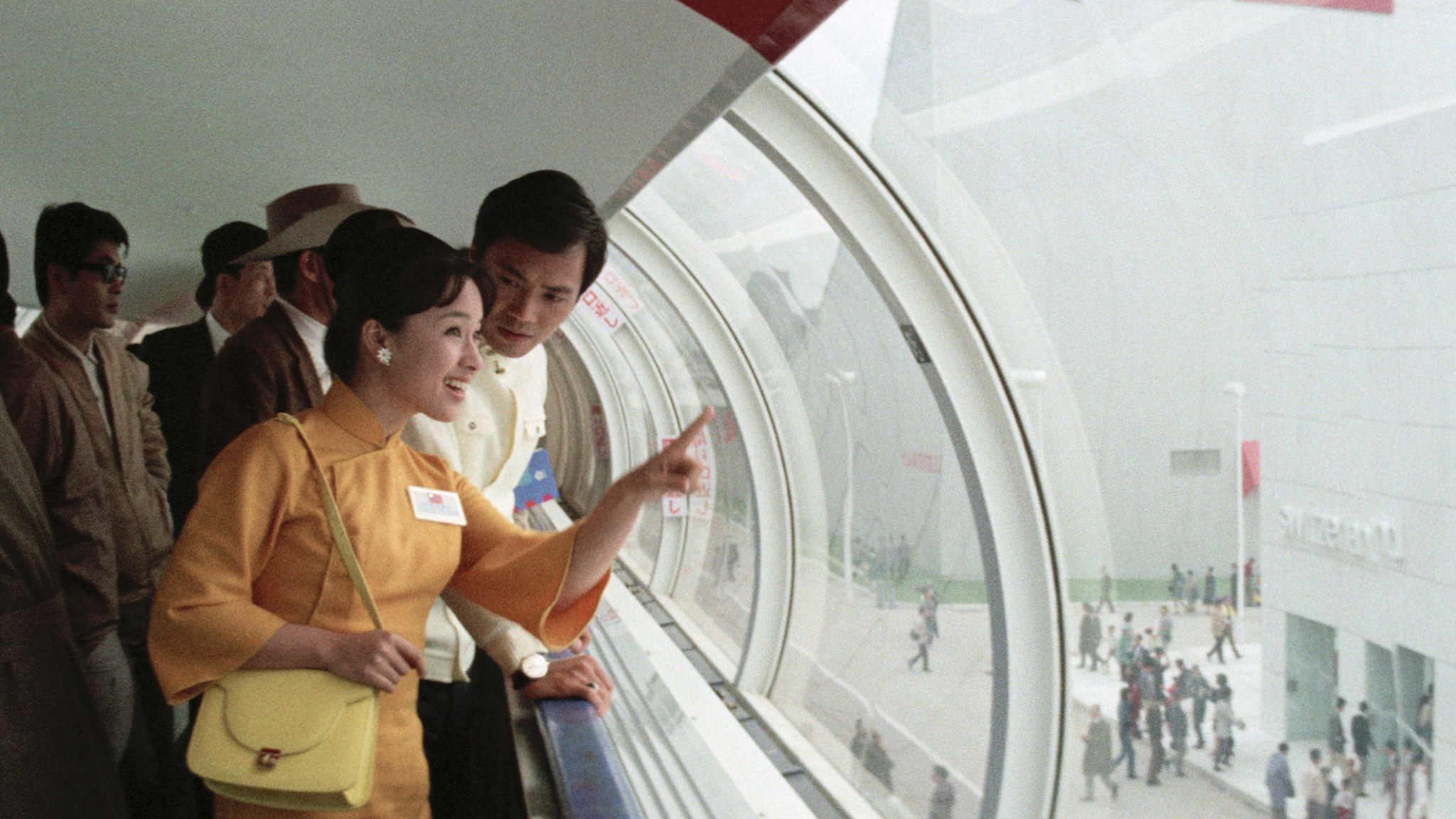

Like Who Killed Teddy Bear? and L’ammiratrice, Liao Hsiang-Hsiung’s Tracing to Expo ’70 (1970) was never meant for posterity and yet, today, feels richer than many more serious-minded movies of its time, Taiwanese or other. Liao offered its audience three different kinds of pleasure in one film: Taiwanese-Japanese singer-actress Judy Ongg putting on a show at the beginning, with some hot tunes of the moment getting cheekily ripped off (yep, that’s Aquarius from Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical you’re hearing, among other late 1960s hits!); then an extensive tour of the Osaka Expo, the first event of its kind to be staged in Asia and a source of collective pride as well as curiosity; and finally a mystery tale with a pretty serious realpolitik edge. All of these aspects had an urgency – the audience of its days wanted to see a star it mostly knew from the radio, as well as an event they had heard and read about but not seen in living colours, and that in a country with which they shared a troubled past many had lived through and remembered. Films could be like that back then: many things at the same time, aesthetic shapeshifters, treasure troves.

Htoo Lwin Myo’s lecture performance essay Time Will Not Tell (2026) is an actual investigation of historical pre-cinema objects: magic lantern slides, the probably oldest art works of common lineage with film, relating views and opinions on Myanmar, or Burma as it was then called. But what did they tell – and what not? What was glossed over, what remained unmentioned? But then, again: What do they tell? A plurality of voices is employed here to get through the thick of history with its many layers and aspects which don’t need to add up – colonial exploitation and the beauty of craft for example can and do co-exist, if uneasily, but still. A completely different approach to a historical find is at work in Santiago Sein’s epic Para hacer una película solo hace falta un arma (2026): the objects, piles of film cans destined for the trash in this case, offer some initial clues about their contents, which slowly leads to the story of a whole generation whose hopes and ideals would be crushed by the 1976 military coup. The images on some of the materials saved from destruction contain shots of people vanished by the junta – now, only cinema as well as the memories of those who survived the years of terror retain traces of their earthly presences.

Film history as a fancy rooted in a story is offered by Bruce Posner with A Philological Quandary, Kenneth Anger’s ¡Que Viva Mexico! (1950) (2025). Its starting point is Sergei Eisenstein as an elective affinity of Kenneth Anger, which the US avant-garde axiom mentioned time and again, as well as the tale of Anger’s personal ¡Que Viva Mexico! edit which seems to have vanished. Posner does not try to (re-)construct-by-speculation what Anger’s take on Eisenstein’s Mexico materials looked like; instead, he offers ideas concerning how Anger’s vision might have functioned by going forth to his Scorpio Rising (1963), its images and rhythm, suggesting via parallelisations of scenes from both works what Anger (probably) learned from dealing with Eisenstein’s images. Historical objects get compared here with a clear idea of what the result shall be – a yearning for a reflection of what hopefully actually happened.

And, so, Cinema Regained is once again a laboratory for film history where the joy of learning and the fun of watching go hand in hand.

Dedicated to the memory of Hartmut Bitomsky and Kari Uusitalo, teachers both, and Yuki Aditya, our friend.

– by Olaf Möller

A list with articles

-

IFFR closes its 55th edition celebrating an uptick in new, younger audiences and industry attendees

Published on:-

News

-

Press release

-

-

Shahrbanoo Sadat’s No Good Men opens Berlinale 2026 among strong HBF and CineMart lineup

Published on:-

CineMart

-

Hubert Bals Fund

-

IFFR Pro

-

-