Critics' Choice VII – Bottled Songs 1-4

04 June 2021

Tara Judah about Bottled Songs 1-4.

Dear Kevin, Dear Chloé,

I am writing to tell you about the pulsing I hear as I sit in the dark, in the early hours of morning, after watching Bottled Songs 1-4. As I listen to it, a self-generated sound, I am wondering if it is more than just the soundtrack to the space between the images, your words, their meaning, and me.

I hear in both your voices a soft melancholy, as you narrate your videos; it’s close to hesitation and yet you both have such clarity in your articulation.

Chloé, your words wound me with their profundity. When you speak, in The Observer, of not being left alone, “Mais la video est tourjous en ligne, elle insiste”, you are so perfectly, yet terrifyingly addressing the paradox of the images you interrogate – and not just those images. That the existence of any image is an insistence is what makes it ghostly; it haunts us by being. And yet, the images of which you speak are and hold literal ghosts, now for their lack of being.

It is painful to think of this. I consume so many images without giving them the space that living begs for. I too have seen lives onscreen that are no longer, and in bearing witness to such images, I have, as you intimate, a responsibility in the construction of their meaning. To watch is a form of participation and to make a living from choosing to speak, write or comment on images – or perhaps not to – is also a form of participation: I make my living watching and deciding whether or not to give space to these ghosts.

When you unveil Les Observateurs France 24 as participants, it feels as though a hand is pressing into the centre of my ribcage. Too often, I forget to think about why an image has reached me, why I am watching it, who decided it was something that should be seen, and how it means that everything I see was someone else’s decision first. My decision is almost always last and yet, it is true that something can be both true and false at once. What I have learnt about historical truth is that it is multifaceted – or perhaps multifaced – as much as the humans who produce it.

There are more meanings than I can comprehend, though I can conceive of their existence, their insistence.

When you speak of Frida Kahlo, I am embarrassed that I did not know about her painted corsets. They are remarkable. They are emboldened by what they hold; once an embodied being, pulsing, and now the silent space that the body wants us to remember. It is visual melancholia – it asks us to mourn that which we did not know. Its colour is as vivid as the colourisation of the photographs that Kahlo helped her father with in the early 1900s. Perhaps yellow was the colour that Kahlo used to highlight what Roland Barthes called the punctum, painting the undergarments of ghosts in her father’s images.

Kevin, you speak of finding yourself searching for “other images” – in the hope that they might help in constructing an understanding; that their context or juxtapositions might give that which is missing.

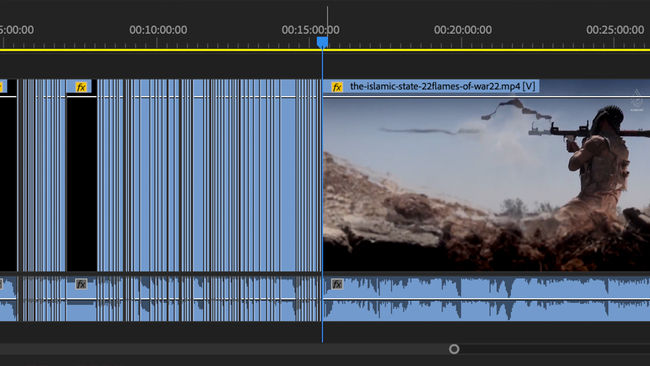

Your research around Flames of War illuminates not only the problem of the material at which you are looking, but also the problems of film criticism, of journalism, and of how we write about, talk about, and position that which we observe.

I am reminded of a film I saw in 2014, Aleppo. Notes from the Dark. I have never been able to talk with anyone about this film, though it is easily enough available to see. I am reminded of it because I wrote about it clumsily and spoke of the aesthetic of blockbusters – just like the critics who wrote about Flames of War. It makes me think about the language critics allow themselves to use, and the reasons why; because it’s what editors want, because they're trying to get paid and have to write for house style, because they're lazy, because they have vocabulary instead of articulation. Because language is currency.

Because the Hollywood blockbuster and Leni Riefenstahl are references we all think we know and understand. They are used not for their accuracy but as language in translation, to evoke, to warn a readership. To produce a palatable understanding of images that are produced to be anything but.

When you speak of being afraid – not only of the images – but of what the ‘act of seeing’ might do to you, I hear the echo of Chloé’s concerns about watching as participating, like Lawrence’s voice. There are even moments when I wonder if I will turn your video off because I don’t want to see what I don’t even think you will show me.

Where do these images ‘belong’ in the unofficially-archived archive of the internet? And how, as a viewer, can I find Kahlo’s gaze; seeing more than what things are, including what they could be? Is it the search for more that quietens the sound of that embodied insistence that the images produce in us?

Your attempt to embody a machine-eye, to see the movie, instead of having to watch it, Kevin, it feels like you’re trying to deconstruct Barthes’ punctum. I wonder what he would say. And I wonder what the digital transitions – the work done in the space between the images – what would he call that? Perhaps it is best described by your visual map. A colourful glitch in linear progression. Maybe there is no name for it.

But if the pulsing stops, then it must be a glitch in the system, mustn’t it?

Can a glitch have a face?

In parts three and four of Bottled Songs, your research becomes personal. You both show, and talk about, people with faces, people with names; people who may or may not still be alive, but whose faces somehow deny that violence around them.

“We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces.” The movies have always loved faces … Emmanuel Lévinas believed the face was an ethical call. An encounter with the Other, a way of being responsible for the Other in the Self.

When T.E. Lawrence encountered anOther – Sherif Ali asked him, “What is your name?” and Lawrence replied, “My name is for my friends. None of my friends is a murderer!”

The screen has long taught me to believe that faces and names bear our humanity. But your research, Chloé, Kevin, it shows me this can be both true and false, at once.

Perhaps this is why we map, along geographical lines, cinematic lines, and embodied lines. We map our way through events so that we might make an understanding of trauma. But those lines, they are grey. The shifting sands of control, of power, and of pulsing lives, create spaces of in-betweenness.

When I look at a map of the Middle East, I am confused. I don’t know those shapes. I know some of the words that the shapes are called. But they are not names, they are stakes. And the flat cartography betrays their height.

I remember being told as a child that my name – Judah – was once a physical place, in what I think is now Iraq. That my name is where I am from. But when I was older, I saw a family tree my aunt had been working on, and I was surprised to learn that somewhere along the way, the name Judah just ‘appears’ – like a replacement for anOther, a more obviously Arabic name. But I can’t remember that name. It’s difficult to be sure about any of the details because the records were sketchy, and I misremember it anyway. I think I remember that the names of the women weren’t recorded on the map until well into the mid 1800s. Or was it the 1900s? I do know that have never seen any of their faces.

There is a space between them and me. I have long thought about interrogating that space, but I don’t know what colour it is. If I mix grey ash and yellow paint, what colour would that be?

It is dawn now, and I am no longer in the dark. Soon the sky will be bright blue, with white clouds, gently tinged with orange. Somewhere in that orange space, between the sun and the clouds, the soundtrack will move on, and my pulsing will give way to birdsong.

Good morning, or perhaps it’s good night,

Yours,

Tara

Critics' Choice VII: On Positionality

For the seventh time, Dana Linssen and Jan Pieter Ekker are organising the context programme Critics' Choice during the International Film Festival Rotterdam.