Critics' Choice VII – Q&A with Morehshin Allahyari & Kevin B. Lee

04 June 2021

This is a transcript of a conversation between Kevin B. Lee and Morehshin Allahyari that took place in the framework of a presentation at the Merz Akademie last May Artist where they discussed speaking positions, privilege and distance, as well as the question if an act of care or an expression of care may exert a violence on others. These topics relate both to the work of Morehshin Allahyari and reflect on issues raised in Bottled Songs 1-4.

Kevin B. Lee

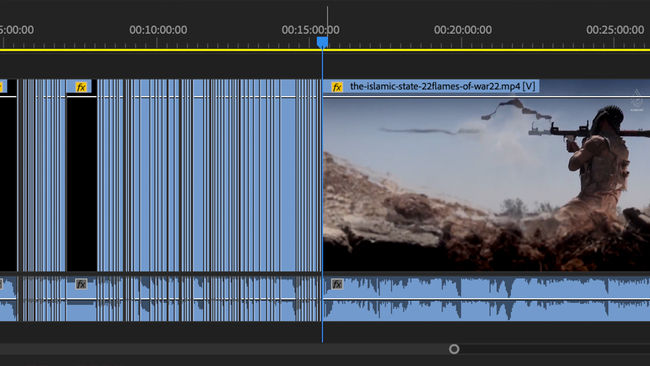

“I should just let everyone know, I didn’t really give this background about how I got to know Morehshin’s work. It was at an online exhibition that included our work. It’s called Re:claim, Art as Resistance against Political Violence. Morehshin gave a presentation there, and her work was included. I myself have been doing research for the last few years about media from the Islamic State and ways of analysing it from the spectator’s standpoint. I will say that, in the years that I’ve been doing this, I’ve become increasingly sensitive and critical about my own interest in this material, and it really has helped me a lot to see an artist like Morehshin and how she positions herself in relation to this material. Really asking this question of ‘What relationships does one have with it?’ And how does it reflect one’s own position in the world? And what right does someone have to engage with any given topic, especially one that’s so politically sensitive?”

“I think, Morehshin, your presentation just now gives a strong account of your own personal development, in regard to asking this question of the politics of We. Because these days, we make a big deal about inclusivity and equality, but your work asks us to take a more considered view of these words, to not take them for granted as these ultimate answers to our problems. And this last work that you showed us definitely puts me in this position that I cannot access it as deeply as others. And so I have to ask myself, what is my relationship to it? My engagement with it? So this word, We, is what I want to ask you about. How has your understanding of this word changed over the years? What does this word We mean to you now?”

Morehshin Allahyari

“I think at the very end of my talk, I talked about this idea of distance. And, to me, it’s important for us when we’re in different positions of privilege to understand what it means to keep distance, right? For example, I was having a conversation recently with a friend of mine. They started these queer Middle Eastern parties in Montreal, where like, it was an Arab and Persian kind of scene. And it was supposed to be kind of like a safe space for people of the region, because there was no space like that.”

“There are many queer white public things that are out there. But then it was important for him to build that space that it was focused more on like, PoC, people of colour. And then they talking about how eventually so many random people came to these parties, then the people who started it just didn’t want to do it anymore, you know? Because it had lost after a while, what it was about for them. And then we talked about this idea of distance, right? How it’s important sometimes for us to be okay with keeping distance, allowing other people to do their thing without always feeling like we also have to be in it.”

“I mean, I feel that way about, let’s say, Black spaces in New York, right? Like where there’s like certain parties or events like Afropunk, for example, which is a festival that happens here, and again, thinking about what it means if I just don’t go, what does that mean? Right? So, it’s I think, I think about, again, from my own place, and like, other people’s inserting yourself into spaces, always like asking what it is that you’re doing. At what point, it’s a soft form of violence. At what point, it’s not necessary for you to be there. At what point it’s okay to let things be. And that kind of extends to these ideas of We are constantly, for example, going back to these cultural heritage sites, or these projects that were happening with these tech companies, or years and years of colonialism, where this language of We has been used as a way to colonise other cultures.”

“So, saying, like, we’re all the same. We’re all human. And this is for all of us. And that language keeps coming back as a way to then justify why it’s okay to take something and take it to another place. And then hundreds of years later, not even willing to send it back to that country that you got it from, for whatever reason, at that time. Let’s say a dark path, a mistake, whatever. But still a lot of museums and spaces are practicing these things, where they’re like, ‘No, we we’re not going to send it back. It’s just part of the museum collection.’ So yeah, for me, it’s been like really important not only in my research and artistic work to always ask these questions, but also in a way that I want to connect to people around me, that I want to connect with the world around me personally, you know, as a person to always ask those questions and think about, again, these ideas around distance.”

Kevin B. Lee

“Yeah, that word Distance is a very relevant word in the last year. And thinking about the politics of distance, how distance was kind of used as a tool of preservation and health but, you know, also became very politically charged about keeping people from being able to meet. It reminds me of something you said earlier in your presentation regarding the politics of the vaccine with vaccine selfies. You give this account of how the vaccine selfie is like an expression almost of violence, of expressing power, the power to get vaccinated, whereas other people around the world are not.”

“Just for the sake of a counter argument, people found it important to have vaccine selfies just to help spread appreciation for getting vaccinated when you had people denying vaccines. It’s so funny, these contradictory perceptions and, you know, ways of interpreting an image. It relates to a term that we were discussing a lot when we looked at your artist’s talk on digital colonialism, the term ‘violent care’, to which one of our students, TJ really asked some important questions. When do we know when an act of care or an expression of care exerts a violence on others? You know, especially when one has good intentions or is meaning to help? How do you diagnose the violent care in any gesture?”

Morehshin Allahyari

“Yeah, that’s a very important question. It’s also almost like asking ‘How can I be a good ally?’ In the US, for example, at a time that there was a lot of conversations around the Black Lives Matter movement, and George Floyd, that was a question that some people would ask. How can I be a good ally to this? How can I know how to help without bringing in any sort of violent care, and again, putting myself in a position of power when I can just be in a position of allyship? Those things are different places, right?

“So it’s not an easy answer. I think one of the best ways to think about it is to always check how much space you’re taking. Because I think so much of this stuff is about taking space, right? And when are the times that it’s important to be an ally by the side of someone, when are the times it’s important to let them be, you know? And that connection and that kind of understanding sometimes comes from having conversations with people around it. I’m talking now more about a personal kind of relationship. Let’s say you have black friends, and the George Floyd thing happens, and everyone is kind of fucked up in the head because it’s like, What the fuck, more of this? And people are going through sorrow, people are going through grieving, people are going through certain things. And there is a long history of this kind of violence, it’s not just a new thing, obviously, in the US and Europe for black people.”

“So, you know, sometimes it’s about asking that friend, is there is there a way that I can help you? Is there way that I can be there for you, rather than just assuming these are the ways they want me to be there for them. So really, it’s a practice of communication. It’s sometimes a practice of willing to be vulnerable about these things, you know? I think vulnerability is also another part of it, like, okay, I might have done this, and it might not have been the right thing. So, I can step away from this and rethink it, and, like, redo it.”

“And I think this is how we all grow. This is how we can all grow together. I’ll give you another example. Let’s say that you work in an institution, and then you want to curate a show, that is about PoCs or a show about the Middle East or indigenous people of a certain land, etc. And as a person who doesn’t come from that space, there are two ways to go. One is that you curate that show, and that’s it. You bring in those people and make those choices. Another way is that you have a guest curator who is from that region, and comes and curates it, or you collaborate with a guest curator. So, these are just examples, ways that I think we can like really push ourselves out of these comfort zones of the immediate thing that comes to our mind, like, Okay, I'm just gonna do this and this is the best way to do it. And instead to always be questioning and rethinking how else you can share a platform, how you can share this space of making these kinds of choices. And again, it’s never an immediate answer. It always comes from, depending on a situation, rethinking these positions of power that we have, these positions of access we have, these positions of privilege we have. Yeah, so I would say it’s the matter of situation to situation, and communication and self-reflection.”

Kevin B. Lee

“That’s beautifully expressed. I just have one more question. But I would also like students to ask any questions themselves. Anyone want to jump in with a question at this time? I think they’re kind of speechless by the level of thinking you’ve presented. Right? Well, yeah, let’s, let’s it’s not all serious. Because one thing I took from, you know, the project with the Jinns [supernatural female figures], is that there’s, dare I say, like an element of play or a return to the power of the mythical, which I also kind of associate with the power of childhood, you know? And I connect the project with your presentation Digital Colonialism, you presented these four objects, which I think have a very strong kind of personal or childhood relevance for you. And it was kind of like going back to objects that your family members and people had given to you that, you know, have really acquire symbolic importance and are full of significance but are invested with this the energy and the memory of childhood, which I find very powerful. Because I think of childhood as being the space of joy, of play of possibility. So, do you find these elements of joyfulness, playfulness, and the energy of childhood to be important for your practice?”

Morehshin Allahyari

“Yes, and no. I mean, when it comes to the stories of Jinn and stuff like that, I think I have really interesting memories of being with my grandmother, and her telling me all these stories. She one time for me a story about seeing a Jinn in a public bath house where Jinn are said to visit more like dark human spaces. So there are a lot of stories about Jinn visiting places like that houses. I remember, we were like lying down on the rooftop. It was like I was with her in the west of Iranian Kurdistan, where she was from, and it was me and like, to two or three other cousins, and she was like, telling us the stories about these Jinn. And I remember how scared I was, but at the same time, I just wanted to, like know, more.”

“So, it was it was like a really like, interesting moment for me in terms of being curious and being scared, but at the same time wanting to know what happened to her. So definitely Jinn stories have like a connection to like, a lot of amazing memories with my childhood. But then there is the dark side, which is growing up during a war, and that was not a fun experience, you know? And then the Kabous project really goes back and looks at that in some personal ways, my relationship to childbirth, or having a child. This is why I have an imagined child that is a monstrous daughter. That then talks about trauma and how, to exit the intergenerational trauma, one must give birth to nonhumans. That’s basically the premise of it. And yeah, so I think it’s a complex relationship to the past.”

Critics' Choice VII: On Positionality

For the seventh time, Dana Linssen and Jan Pieter Ekker are organising the context programme Critics' Choice during the International Film Festival Rotterdam.