Mayday − Island of Lost Girls

27 January 2021

For each of the features in competition, IFFR asked a critic, writer, academic or programmer to write a short reflection in a personal capacity. The resulting series of ‘Appreciations’ aims to encourage viewers − and filmmakers − at a time when there is no physical festival. Beatrice Loayza shines a light on Mayday.

The novel-turned-Disney property, Peter Pan, takes place in a fantasyland of eternal childhood, though curiously, girls remain absent. Untethered from their families, J.M. Barrie’s ‘lost boys’ lead a life of whimsy and adventure among evil pirates and mermaids. “Are none of the other children girls?” Wendy asks Peter Pan before being whisked away to serve as the group’s den mother. “Oh no; girls, you know, are much too clever (…).”

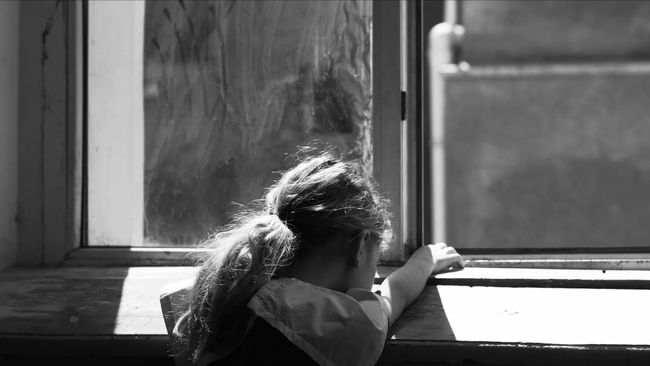

As if responding to Peter’s assertion, Karen Cinorre’s Mayday imagines an island of lost girls, rendering boyish escapades into a fierce rejection of the patriarchy and its underpinning mythologies. Every little girl dreams of her wedding day, or so the stereotype holds. Mayday begins on such a day, only to reveal the rot beneath the surface. Our protagonist, Ana (Grace Van Patten) is no bride, but rather a weary member of the wedding venue’s staff. Cut down by her abusive employers, and the drudgery of her life, Ana slips into another realm by a stroke of magic. An electricity-zapping storm brings her to a secluded island inhabited by Marsha (Mia Goth) and her gang of giggling misfit ladies (Stephanie Sokolinkski and Havana Rose Liu). Dressed in World War II-style uniforms and well versed in the art of combat, they take it upon themselves to exterminate any male soldier who finds his way onto their turf. And by radio dispatch, the girls cry ‘Mayday’ and play damsels in distress, sending many eager heroes to their certain death.

With shades of Louis Malle’s Black Moon (1975), Cinorre instils both dreamy childlike wonder and brutality into her surrealist battle of the sexes. We’re introduced to a world seemingly mapped out from the inside of someone’s head, yet this reality − a haven of rugged sisterhood and coastal wildlife splendour − is also marked by trauma, violence, and distrust. The soldiers, always hiding out in the forest or parachuting in from above, pose constant threats, even if they look more like boys than men. Marsha wants to kill them all for what they’ve done to her, but Cinorre understands that misandrist vengeance can only achieve so much. These soldiers, vehicles of terror, but also symbols of naive masculine duty, are themselves trapped. The film suggests an alternative in the joys of creative expression and performance: when Ana stumbles upon the enemy’s camp, an upbeat musical interlude replaces the expected armed showdown. It’s a welcome dose of camp silliness seemingly out of left field, but in step with the film’s boundless spirit and uncanny humour.

If Neverland represents the escapist impulses of young boys, where does that leave ‘clever’ girls with the urge to forget and break free? Delicately underscoring this ambitiously imaginative tale of healing and self-realisation is a sombre recognition of how suicide figures in Cinorre’s creation of lost girls. Ana’s descent into the rabbit hole, after all, is prompted when she sticks her head into an oven. Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999) comes to mind, but rather than observe young women from the purview of male fantasy, Mayday takes a bold step in drawing a portrait of female desperation without the pity and scandal. Rather, it abounds with a sense of possibility and hope.

Beatrice Loayza is a Peruvian-American writer and critic based in Washington, D.C. She has written for Film Comment, L.A. Review of Books and The Guardian.

Appreciations

‘Appreciations’ aims to encourage viewers − and filmmakers − at a time when there is no physical festival. Discover more short reflections on the features in competition.