Black Medusa

28 January 2021

For each of the features in competition, IFFR asked a critic, writer, academic or programmer to write a short reflection in a personal capacity. The resulting series of ‘Appreciations’ aims to encourage viewers − and filmmakers − at a time when there is no physical festival. Joseph Fahim shines a light on Black Medusa.

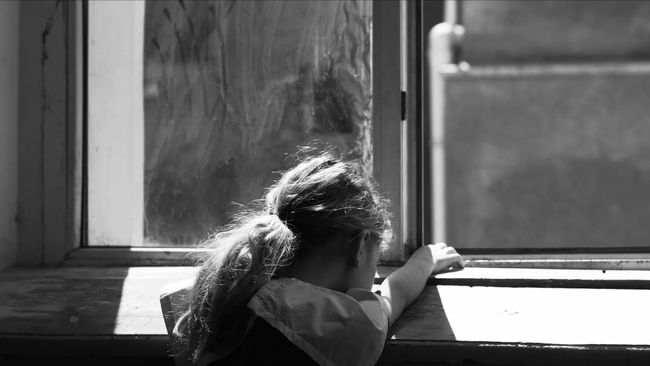

For most of its 96-minute duration, Nada (Nour Hajri), the deaf, mute protagonist of ismaël and Youssef Chebbi’s Black Medusa, has a blank stare − a blank canvas. Fleeting pronounced emotions occasionally break its composure: pain endured, savage zest in inflicting pain, and a palpable lack of satisfaction. But these are evanescent moments, unwillingly seeping from the young woman’s carefully self-constructed guise.

For most of the running time, Nada remains a cypher, and not just because she can’t speak. Little is revealed about her background; little is revealed about the motivations behind the killing spree she embarks on from the very beginning of the film until the end. What we know is that she’s been sexually assaulted. She’s been violated. She’s angry, and she wants blood.

Black Medusa may appear simple, bareboned, rather minimal, in its narrative structure. Yet in adopting such an elemental narrative, ismaël and Chebbi have succeeded where many male directors have failed: presenting an authentic, honest portrait of a raped woman who, in an uncharacteristic deviation from Arab film, refuses to be victimised. After all, how can any man capture this full spectrum of trauma? How can any man accentuate the anguish, confusion and loss sexual assault survivors experience?

Arab cinema has no shortage of rape-revenge movies − a sub-genre that flourished particularly in Egypt in the 1980s and early 1990s. In contrast to its forebears, Black Medusa eschews psychology, presenting instead an impressionistic portrait of a woman on a quixotic quest to eliminate the fundamental source of violence in her life by using the same method: by reversing the dynamic of power in her favour.

Inspired by Abel Ferrara’s cult classic, Ms. 45 (1981), Black Medusa conversely offers no cathartic charge associated with 1980s exploitation cinema. It similarly offers no easy or straightforward answers, knowing that revenge can never be a panacea. The monochrome cinematography augments Nada’s growing detachment from her petty prey. Killing is soon transformed from a self-validating act for enacting justice into a mechanical obsession: a fixation that grows into her main raison d'être.

Its moral and philosophical complexity aside, there is, admittedly, a primal enjoyment in seeing Nada tearing her male victims apart. Tunisia has undeniably made strides in advancing women’s rights, yet patriarchy still defines the relationships between men and women across the Arab world, both in the street and in courts of law. Black Medusa is thus a revenge fantasy for the #MeToo generation: a fable of sorts that restores to women their agency while deliberately reducing the destructive, entitled male impulse to repeated, static gestures, committed by hordes of indistinguishable, faceless men.

For the past three decades, North African cinema has mined every imaginable narrative of the subjection of women and toxic patriarchy. In injecting cinematic violence into the proceedings, ismaël and Chebbi have put a fresh, daring twist on what has recently become a dated equation; the pair have shunned the predictable, exportable realist discourse and given us the Arab rape-revenge of the century. Playful and serious-minded in equal measures, the physical rage of Black Medusa ultimately transpires into an act of defiance against a system that vigorously ascribes formulated roles for women. Even on screen.

Joseph Fahim is an Egyptian film critic, programmer and lecturer. He is a former member of Berlin Critics' Week and former director of programming at Cairo International Film Festival.

Appreciations

‘Appreciations’ aims to encourage viewers − and filmmakers − at a time when there is no physical festival. Discover more short reflections on the features in competition.