The Year Before the War

27 January 2021

For each of the features in competition, IFFR asked a critic, writer, academic or programmer to write a short reflection in a personal capacity. The resulting series of ‘Appreciations’ aims to encourage viewers − and filmmakers − at a time when there is no physical festival. Dominik Kamalzadeh shines a light on The Year Before the War.

Modernity’s dialectic forces − a deep distrust of governments, corrosive social energies and a growing belief in science and the occult − have made Pre-War Europe a permanent source of inspiration, and even more so in our own troubled era. This has resulted in very different filmic approaches, such as László Nemes’ kaleidoscopic parable of rising fascism in Budapest, Sunset, or a Netflix series like Marvin Kren’s Freud, in which the father of psychoanalysis-turned-profane detective chases a female murderer with the help of hypnosis.

Elements of both films can be found in Dāvis Sīmanis’ The Year Before the War, and given that the Latvian director’s film intersects with a variety of generic themes and topics of the era, this is not all that surprising. He constructs a maze of ideological battles (be it societal renewal movements, rising nationalism or anti-Semitic superstition) which slowly build up to the foreboding of an impending war, and even more, the empires of fear to come.

As the story of an everyday young man, Hans (Petr Buchta), a bellhop in a hotel, The Year before the War prefers uncertainty over narrative clarity: The hero is mistaken for a mysterious doppelganger named Peter (perhaps a reference to Georges Simenon’s novel The Strange Case of Peter the Lett), who is chased by mobs on the street but resists indoctrination from political demagogues (a glass-eyed version of Lenin), esoteric gurus, and giggling ‘mad scientists’ like Freud himself. You might call him the unwilling protagonist of history’s own blind inner dynamics − a less-focused, shaken double of the anarchist Mikael Bakunin.

Escaping from Vienna, Hans follows a mysterious female activist, his own Mata Hari, first to the nudist commune, the so called ‘vegetable cooperative’ in Monte Verità in Switzerland’s Ticino, where he takes a short romantic break; then to Paris, only to delve even deeper into troubles, getting blamed for plotting, murder and political incitement. Early on in the film he asks for a pistol in a library. It’s a moment when you already suspect he’s not going to use it like a man with a noble mission: he just stumbles from one setting to the next, haunted by ghosts and turning more paranoid by the second.

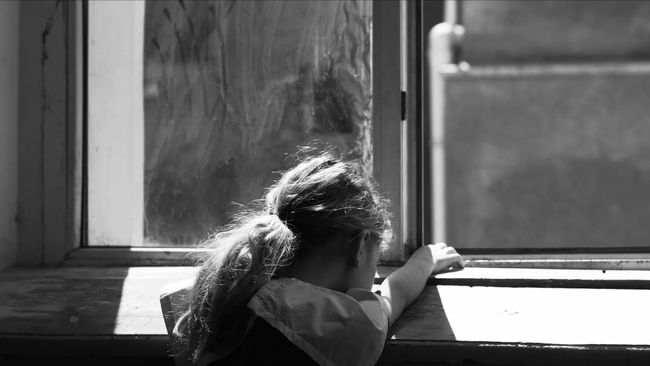

Sīmanis’ film was originally shot by DP Andrejs Rudzats in colour, but is presented in black and white, consciously alluding to early silent cinema, although the imaginative use of mise en scène and at times delirious montage is obviously much more diversified. Visually often stimulating, especially in its use of landscapes such as snow-white mountains to emphasise the psychic state of its protagonist, the film shows a predilection for the carnivalesque in its depiction of its characters. In particular all manner of authorities, political agitators or doctors of the human soul, behave in a strangely childish manner, as if they have engaged in a few too many self-experiments.

The dialogue aims to give an impression of the Babylonian mixture of the languages of emigrants, an effort that requires scrupulous language coaching. Nonetheless, in his most convincing moments Sīmanis creates his very own understanding of Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, who turns his face toward the past and sees a catastrophe of debris piling up before him. People with skulls on their clothes rally in the streets, and a future that will only reward those who play by the rules is about to commence.

Dominik Kamalzadeh is an Austrian film critic and journalist and co-editor of the magazine kolik-film.

Appreciations

‘Appreciations’ aims to encourage viewers − and filmmakers − at a time when there is no physical festival. Discover more short reflections on the features in competition.